Risk assessment for PAH

Risk assessment is a critical component of a guidelines-supported, goal-oriented, comprehensive treatment approach for patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Risk‑assessing your patients at diagnosis and every 3 months throughout their care helps you predict their survival, assess their progress toward treatment goals, and determine time when treatment adjustments are needed.1

What is risk assessment?

Risk assessment is a mathematical method to combine patient variables and estimate their mortality risk. Risk assessment provides an objective means to evaluate your patient’s disease status and estimate their prognosis.1,2 Knowing a patient’s calculated risk score informs treatment goals, medication regimens, and monitoring decisions.1,2 A risk score is derived from a variety of inputs—including clinical and functional assessments, biomarkers, Echo measurements, and hemodynamic parameters—to estimate their risk of death (or, conversely, their chance of survival) over 5 years.1,3,4

Risk assessment built on large registries

As a rare disease, PAH has been difficult to study. Multicenter, observational registries focused on PAH were initiated in countries around the world to study the course of disease and disease management. Risk assessment methodologies are based on these robust, multicenter registry data of patients with PAH.2,5 Registries include the US-based REVEAL and the European-based COMPERA, French, and SPAHR databases.5-7

Risk assessment is based on parameters collected from these large, longitudinal databases of real-world patients.5-7 Using consistent patient variables and registry-specific algorithms, survival of patients with PAH can be predicted up to 5 years from diagnosis.1,3,4,7

These calculations—or risk scores—indicate the prognosis of patients at various risk strata based on inputted patient variables.7

Calculate risk using online risk calculators

Explore Risk Calculators

The Importance of Risk Assessment

Discover why formal risk calculations are essential and the latest tools available to you.

Risk assessment guides treatment

Essentially, risk assessment helps you set and measure objective treatment goals so you can determine treatment plans and evaluate success.1 It is the foundation from which the PAH guidelines build their care plan recommendations.1,7 According to treatment guidelines, achieving and maintaining low-risk status is the primary treatment goal for patients with PAH.1 Patients who achieve this goal improve their likelihood of survival, which underscores why treatment adjustment is needed for patients who are not at low risk at first follow-up.1,3

Predictions using risk assessment

Risk assessment helps predict clinical worsening in patients with at least 1 year of follow-up data. Using REVEAL 2.0, a 0-4 risk score predicts a greater percentage of those patients will be free from clinical worsening than patients with risk scores of 5-6 (hazard ratio, 1.23; 95% confidence interval, 1.21-1.25).2

Risk assessment also helps predict survival. In the French Registry, transplant-free survival was assessed by the number of low-risk criteria present at first re-evaluation in patients (N=1017).6

- Low-risk parameters investigated6:

- WHO/NYHA FC I/II

- 6MWD >440 m

- RAP <8 mm Hg

- CI ≥2.5 L/min/m2

- Patients who achieved low-risk status for all 4 parameters at first follow-up within 1 year after diagnosis had 91% transplant-free survival over 5 years.6

Kaplan-Meier transplant-free survival estimates at follow-up (P<0.001)6:

- 4 low-risk criteria: Transplant-free survival (%) is ~96% at 3 years and ~91% at 5 years

- 3 low-risk criteria: Transplant-free survival (%) is ~92% at 3 years and ~82% at 5 years

- 2 low-risk criteria: Transplant-free survival (%) is ~80% at 3 years and ~63% at 5 years

- 1 low-risk criterion: Transplant-free survival (%) is ~67% at 3 years and ~52% at 5 years

- 0 low-risk criteria: Transplant-free survival (%) is ~42% at 3 years and ~34% at 5 years

Why is risk assessment foundational to care decisions?

Risk assessment guides treatment and monitoring plans to help patients reach low risk.5,7

Risk assessment provides timely guidance

Since PAH can progress rapidly without outward signs of worsening, regular risk assessment can provide timely guidance for patient care.8-10 A formal risk assessment using an objective methodology is established at baseline, re-assessed within 3 months of initiating therapy, and repeated every 3 to 6 months to follow your patient’s progress and catch disease progression.1

Applying risk assessments throughout your patient’s treatment journey will provide information to help you modify their care plan, with the goal of achieving low-risk status. Risk assessment guides treatment decisions, with the opportunity to improve prognosis, particularly when the low-risk goal is met in the first year of diagnosis. 2,3,7

“Never before has risk assessment been woven throughout the entirety of guidelines. Very, very important. Important to assess risk at baseline, which we’ve done. Equally important to reassess patients frequently, generally every three to six months, with risk reassessment at that time as well—our goal being to drive risk to the low-risk category. And only with frequent reassessment is that possible.”

— Scott Visovatti, MD, Associate Professor of Medicine and Director, Pulmonary Hypertension Program, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH

Today’s treatment goals: low-risk status and near-normalization of right heart1,11

Achieving and maintaining low risk is the primary treatment goal set by the 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines and supported by the 2024 WSPH proceedings for patients with PAH.1,11 Additionally, striving for near-normalization of right heart is critical for patient management, as survival is linked to improvement of right heart function.11 Risk assessment provides an objective means to monitor and assess how your patient is moving toward these goals.1,2

Historically, treatment decisions were based on monitoring a patient’s symptoms and escalating therapy when patients showed signs of decline. The approach to treatment has evolved dramatically. Today’s approach uses objective methods to predict outcomes.1,2 With these outcomes, providers can proactively manage treatment plans against specific goals, rather than reactively adjust when patients decline.

According to treatment guidelines, risk assessment should be conducted at diagnosis and then every 3 to 6 months.1 This allows you to1:

- Identify your patient’s prognosis, and set treatment goals

- Determine your patient’s initial treatment regimen

- Objectively monitor your patient’s response to treatment

- Identify RV changes before symptomatic progression

- Escalate therapy to improve risk status when not at low risk

Baseline risk assessment at diagnosis

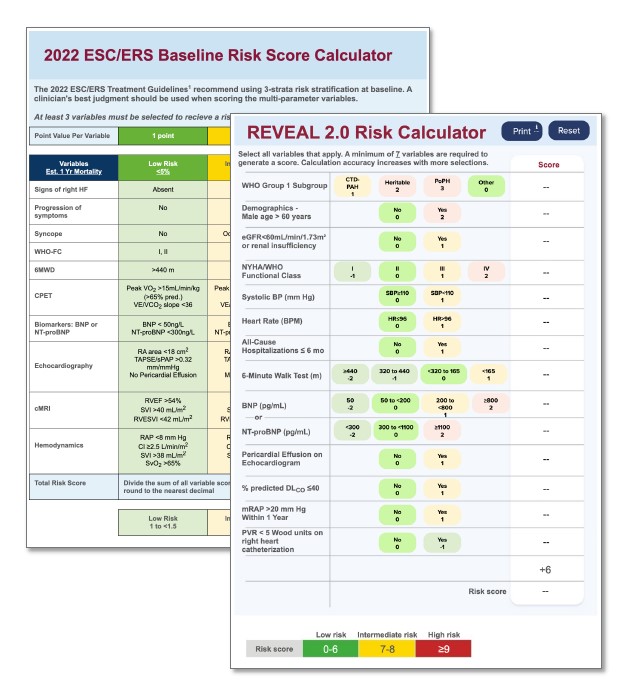

No single patient variable can give enough information to determine management and care.11 At diagnosis, ESC/ERS Treatment Guidelines and 7th WSPH Proceedings recommend evaluating multiple patient parameters, including data collected from clinical assessments, biomarkers, exercise tests, hemodynamics, and Echo evaluations.1,11,12

Robust assessment required at diagnosis

Gathering as much data as possible at diagnosis establishes a strong, comprehensive baseline of your patient’s risk status. This information allows you to objectively assess the severity of their disease, predict their prognosis, and set their initial treatment plan.1,11,12 Knowing where your patient is starting from helps inform your management decisions to move them toward the goals of low-risk status and near-normalization of the right heart in their first year of treatment.1,3,11,12

Multiparameter risk calculations are the foundation of patient care plans

An objective, multiparameter risk calculation completed upon diagnosis establishes the patient's baseline risk status.1,11,12 Experts recommend using as many parameters as possible for this evaluation, which should at least include disease type, 6MWD, hemodynamics, NT-proBNP, and WHO FC.1,11

Examples of parameters included in risk assessment1

WHO FC

6MWD

NT-proBNP plasma levels

Clinical signs of right heart failure

Syncope

Hemodynamics

Imaging (Echo, CMRI)

Progression of symptoms

Importantly, the results of a multiparameter risk calculation guides both treatment goals and initial treatment regimen. They can also be used to formulate your plans for monitoring your patient.1,2

REVEAL 2.0 Risk Calculator and 2022 ESC/ERS Baseline Risk Score Calculator are multiparameter risk calculators for initial, baseline patient risk assessment.11

Initial Therapy Choices and Treatment Goals

Learn how our hosts determine initial therapy for their patients.

Follow-up risk assessments

It is critical that patients strive to achieve low-risk status in their first year of therapy.1,3 In a study of patients who were at intermediate risk at 1 year after diagnosis, only 12% made it to low risk at year 3, while 43% had a lung transplant or died.3 By monitoring your patients in the first year with frequent follow-up risk assessments, you can determine whether their treatment plan should be adjusted in time to achieve the crucial goal of low-risk status in the first year of therapy.1,3

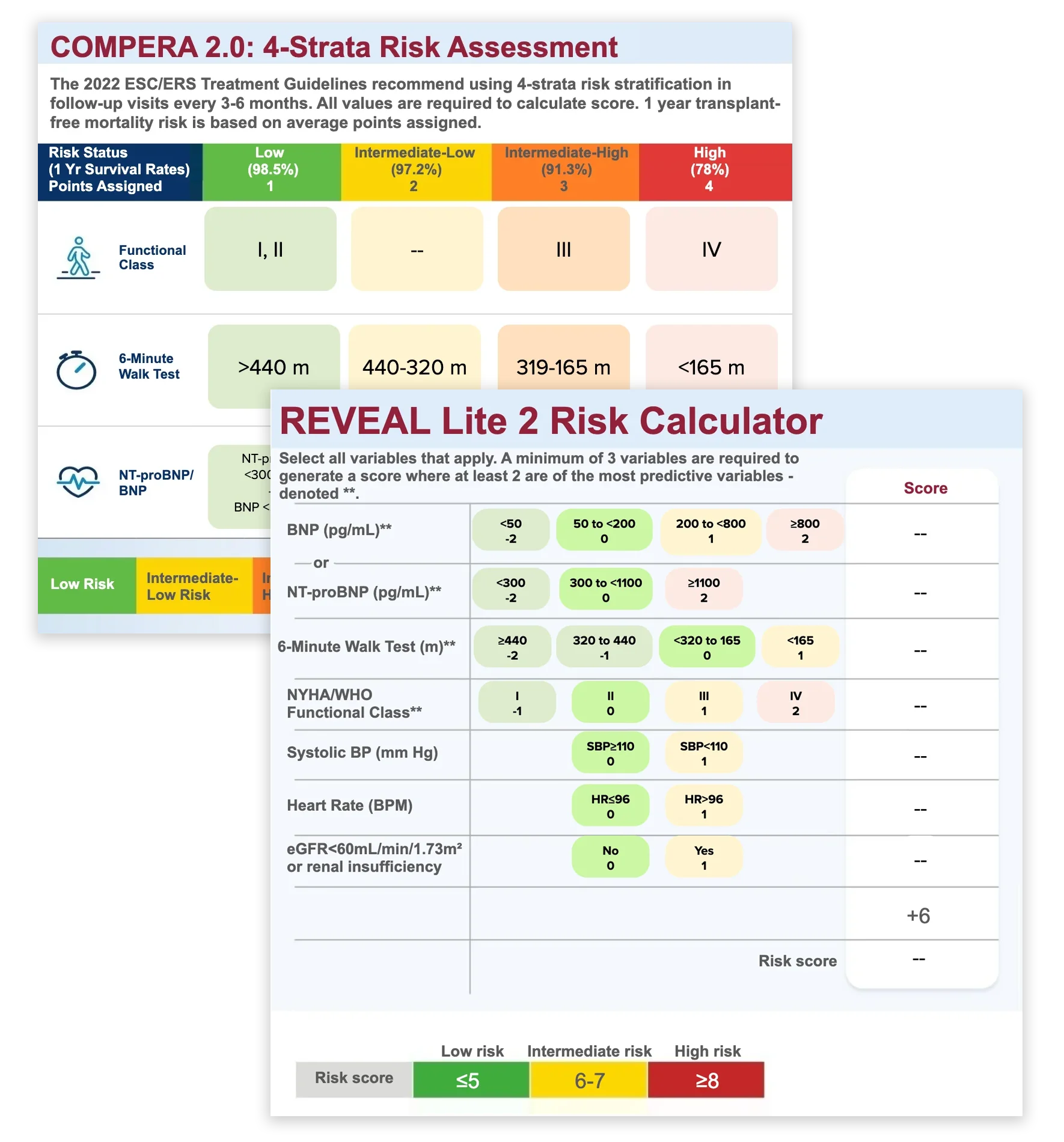

A more granular view of intermediate risk is needed at follow-up

Most patients (63.9%) are intermediate risk at first follow-up. To better understand intermediate risk patients, a more granular, 4‑strata risk model divides intermediate risk into 2 strata: intermediate-low and intermediate-high. This detailed model is sensitive to prognostically relevant changes across the spectrum of intermediate-risk patients. Indeed, it reveals the difference in 5-year survival rates of 67% in intermediate-low and 47% in intermediate-high risk patients.7

These refined risk strata can guide therapy adjustments to help intermediate-low and intermediate-high risk patients reach low-risk status.7 REVEAL Lite 2 Risk Calculator and COMPERA 2.0: 4-Strata Risk Assessment are 2 risk calculators used for follow‑up risk assessment.11

Overall, frequent risk assessments are key to your patient’s outcomes, as they1:

- Determine progress toward the goal of achieving low risk2

- Guide timing of treatment modifications

- Refine treatment options for escalation, particularly among intermediate-risk patients

- Monitor prognosis in patients with hemodynamic concerns

For patients not at low risk: Prompt adjustments to treatment plan are recommended1

Therapy Escalation

Learn how to clinically apply risk status to determine when to escalate therapy and help improve patient prognosis.

“Risk also helps fuel our approach to treatment, escalation of therapy based on risk. Critically important.”

— Scott Visovatti, MD, Associate Professor of Medicine and Director, Pulmonary Hypertension Program, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH

Calculate risk with these resources

The PAH Initiative provides print and online resources to make

multiparameter risk calculation even easier.

Choose the

resource that works best for your practice.